Siva can dream it for you wholesale

I’ve put together sequences from two documentaries: one on the making of Ridley Scott’s 1982 ‘Blade Runner’ based on Philip K Dick’s ‘Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep’, and another on Alejandro Jodorowsky’s attempt in 1975 to make a film of Frank Herbert’s SF epic ‘Dune’. Both sequences are about Dick’s and Jodorowsky’s reactions to the work of special effects maestro Douglas Trumbull, most famous for Kubrick’s ‘2001’ and Trumbull’s own ‘Silent Running’.

I think that between their contrasting reactions to Trumbull – stunned amazement at what his studio could produce, and a rejection of Trumbull’s credentials as a yogi, in effect – there’s an interesting point to be drawn out about the nature of cinema and a respect in which Indian films, from the silent period onwards, have differed from cinema in the Occident.

Science Fiction, mechanical marvels, the supernatural, flights of fancy, and stage magic have been pivotal to each development of Western cinema: from the early experiments with trick photography of pioneers like Georges Méliès and George Albert Smith to recent developments with 3D like ‘Avatar’ and the commercial success of digital animation. (Smith was a showman and huckster who had a career faking photographs of ectoplasm – and a muscle reading and mentalism music hall act, here in Brighton – before his venture into film).

The father of Indian cinema, Dadasaheb Phalke, was a stage conjuror and friend of the German magician and Lumiere Brothers’ employee Carl Hertz. His first film – and the first Indian feature film – ‘Raja Harishchandra’, features the Gods making a physical appearance in human affairs, 98 years before Sir Kenneth Brannagh’s ‘Thor’ and 50 years before Ray Harryhausen’s ‘Jason and the Argonauts’.

The contrasting reactions of Jodorowsky and Dick in the Seventies and Eighties to the edifice of Trumball’s Art are especially interesting to me in view of the changes that are happening here in the future, in the early decades of the Twenty First Century, with the distribution of filmed drama in the American part of the English-speaking global entertainment industry. Amazon’s made an intriguing choice in Philip K Dick’s ‘The Man in the High Castle‘ as source material on which to base a pilot for its new “content”, delivered directly to viewers over the internet rather than broadcast through the air or distributed to movie theatres.

Like ‘House of Cards’ on Netflix and Amazon’s recent hit with ‘Transparent‘, the pilot has been well-received critically and demonstrates that “franchises” (on which Hollywood’s business model is now based) can – through nuanced performance and visualisation spread out over many week’s viewing – have all the depth of story-telling found in a novel. This possibility has been suggested before, by the first two ‘Godfather’ films and by movie projects produced for sequential showing on television as well. This is something which German cinema has monopolised historically: in Wolfgang Petersen’s ‘Das Boot‘; and the vast interlinked narratives of Edgar Reitz’s ‘Heimat‘, Fassbinder’s ‘Berlin Alexanderplatz‘. In terms of the gap between what can be imagined – the scale of film-makers’ ambitions – and what ends up on screen, the only crucial differences between movies and TV now seem to be: the resources at the Director’s disposal; and, integral to that, whether or not the main feature’s selling you over-priced popcorn in the theatre and toys once you get outside, or advertising on the screen. Other than that, if it can be imagined it can be filmed. That includes imagining characters with rich interior lives that take many hours of viewing to fully understand. The scope of what’s technically and economically possible reaches deeper below the surface of waking reality than only imagining what the viewer can see; it also extends to what the audience can feel.

A parallel universe story Executive Produced by ‘Blade Runner’ Director Ridely Scott, ‘The Man in the High Castle’ depicts a divergent timeline where Japan dominates the Western seaboard of the United States after an Axis defeat of the Allies in World War Two. A key divergence from Dick’s novel is that the anti-fascist book-within-the-book ‘The Grasshopper Lies Heavy’ which brings the resistance together is now newsreel footage of an alternate reality, which includes film of the D-Day landings and the defeat of Nazi Germany and Japan. As well as being a more televisually resonant plot device, the addition of newsreel footage to Dick’s story – film which may or may not be faked – is in keeping with one of his preoccupations as writer, and is also one of the main themes of his novel. Both the fact of seeing something depicted which seems real, but which the characters know can’t be real, and the means of distributing those images are made central to the building drama.

To any hardened Phil Dick nut (like me) this is a tantalising nod in the direction of the excerpts of PKD’s sequel to ‘The Man in the High Castle’ included in Lawrence Sutin’s ‘The Shifting Realities of Philip K. Dick’, where Gestapo paratroops travel to a parallel world in which Germany was defeated but where there are nuclear weapons that the Nazis can bring back to their universe. It looks as though an ongoing Amazon series would involve more than just centrifuges crossing timelines. Dick planned the first novel to be a series, like Frank Herbert’s ‘Dune’, which could be more mass market and so could have solved his constant financial problems. As with so many things that Phil tried, it never worked out because of his chaotic lifestyle; and also due to the psychological burden of thinking about Nazis so much.

Dick thought the sequel could be a collaboration with another author:

“Somebody would have to come in and help me do a sequel to it. Someone who had the stomach for the stamina to think along those lines, to get into the head; if you’re going to start writing about Reinhard Heydrich, for instance, you have to get into his face. Can you imagine getting into Reinhard Heydrich’s face?”

In a way, the Amazon series may be that collaboration. In the long term it could achieve what German-American author Philip Kindred Dick clearly intended to do with the books, which was to explore how the global defeat of fascism wasn’t a foregone thing so maybe people should be more vigilant in watching out for the next bunch of hired goons in self-made uniforms. (Maybe they’ll stitch their own name into pinstripes next time?) Dick saw this coming with the Nixon administration’s crackdown on students in his former home of Berkeley, and in the Watergate scandal. He didn’t live long enough to see the Bush W and Obama administrations overseeing the creation of a surveillance state straight out of his stories like ‘Minority Report’ and ‘Flow My Tears the Policeman Said’, with the government of one country – America – able to read everyone’s letters and listen to their phone calls, pre-empt their thought crimes and kill their kids with robot planes if they don’t like what they hear.

Filmed drama is now able to make the impossible look and feel realistic. Hey consumers in America or Britain or India or China or Japan, or which ever mass market the “content” is intended for. Do you want to see a world run by cold-blooded authoritarian maniacs? Well here it is. When you’re done watching Amazon’s ‘The Man in the High Castle’, hold up a miror to your reality and see if you can tell the difference. I like to think Phil would be especially pleased that the show’s “studio”, Amazon, has in recent years hired no-kidding fascist goons to herd its underpaid immigrant workforce to its work camps. Sorry, I mean its “warehouses”. Black uniformed goons from a company called ‘HESS Security’ no less. You couldn’t make it up, even if you were Philip K Dick. The irony of Amazon delivering this vision of a plausibly deniable fake universe where monocultural fascism won… sending pocket-sized chunks of that alternate reality directly to a device in your home by the path of least resistance and without the need for unionised labour…. it’s so triumphant it would make Leni Riefenstahl weep. Not only does ‘The Man in the High Castle’ make the impossible look real, more importantly: it’s directly in your face. It feels real too.

Indian films have never shied away from depicting the fantastic, or from big and costly production numbers. Until the big budget Ranjinkanth vehicle ‘Enthiran’ (‘Robot’), audiences and producers hadn’t sought out spectacle in the sense of Christopher Nolan’s ‘Inception’: the realistic depiction of the impossible. When one or many of India’s cinemas adapts (i.e.: rips off) Nolan’s films, you get the hyper-real version rather than the muted blue monochrome one. There weren’t musical numbers in ‘Memento’ that I recall. If they were in the idiom of Nineties’ trip-hop-lite – for which Indian cinema of the Norties had an inordinate fondness – I think I’d remember. I would have tattooed somewhere on my body “Skip to end credits of ‘Memento'” and “Kenny G does Enigma”. (Though, to be fair, the music in ‘Ghajini’ is quite pretty).

Indian films have never shied away from depicting the fantastic, or from big and costly production numbers. Until the big budget Ranjinkanth vehicle ‘Enthiran’ (‘Robot’), audiences and producers hadn’t sought out spectacle in the sense of Christopher Nolan’s ‘Inception’: the realistic depiction of the impossible. When one or many of India’s cinemas adapts (i.e.: rips off) Nolan’s films, you get the hyper-real version rather than the muted blue monochrome one. There weren’t musical numbers in ‘Memento’ that I recall. If they were in the idiom of Nineties’ trip-hop-lite – for which Indian cinema of the Norties had an inordinate fondness – I think I’d remember. I would have tattooed somewhere on my body “Skip to end credits of ‘Memento'” and “Kenny G does Enigma”. (Though, to be fair, the music in ‘Ghajini’ is quite pretty).

India’s animation industry is still in its infancy, relatively speaking, providing huge numbers of expert technicians to foreign films (the credits of any Marvel film now include a small army of Tamil, Punjabi and Marathi surnames) but without Indian subject matter for films yet, in the way that Jorge Gutierrez’s ‘The Book of Life’ has captured something that’s distinctively Mexican in animation. Arguably, Nina Paley’s ‘Sita Sings the Blues’ comes nearest, and for her trouble in lovingly animating Sita’s story from the Ramanyana the American caught a ton of cow faeces from self-appointed right wing gate keepers of Hindu tradition.

The different attitudes to magic and the magical act of materialising something from the imagination – like a city of the future, Hitler and Speer’s dreams for post-War Berlin, a robot, a God – into a kind of reality on screen is what draws audiences to cinema in India and the European cultures, but their responses to the attenuated reality of what’s being depicted are different. Whereas the idea of spiritual reality in an Islamic and Judeo-Christian context is that something either exists or it doesn’t (Christ manifests in the Communion host bodily, or not at all) it’s possible in the polytheistic, prismatic spiritual reality of India for icons to exist in a kind of state of quantum superimposition, having multiple and simultaneous meanings: a picture of a god or a loved one – or for an actor portraying a god or historical figure – can be both a literal manifestation of an aspect of that personality, and just a picture or a performer playing a role in a drama.

Wittgenstein observes in his ‘Remarks on Frazer’s Golden Bough’:

Kissing the picture of a loved one. This is obviously not based on a belief that it will have a definite effect on the object which the picture represents. It aims at some satisfaction and it achieves it. Or rather, it does not aim at anything; we act in this way and then feel satisfied.

The impulse which drives people to believe that an actor on the screen or stage is a real person is a similar impulse to one that drives people to believe that an image of a god, or a ritual pattern, brings us closer to something bigger than ourselves, or takes us beyond the immediate scope of our perception. That impulse isn’t logical or illogical any more than the impulse to drink water when we’re thirsty is logical or illogical. The aim, in drinking to quench thirst, isn’t the water; the aim is to divert the feeling of thirst. The illogical thing would be to think that the Los Angeles of November 2019 in ‘Blade Runner’ will literally exist in four years time, because we’ve seen it in a movie.

Not all belief in magic, in an Indian context, seems to be literal in that the orthodox and unorthodox responses to it aren’t as clearly codified and reinforced as they are in most Islamic and Judeo-Christian institutions. There isn’t an externally and preordained “aim”, like a ladder to salvation, purity, away from original sin. It’s more a matter of staying in the game by doing more rituals and praying more. Usually till your last breath. (Philip Dick wrote extensively about these topics, as it happens, especially about what was fake and what was real, and about what it was to be an authentic human being. He concluded only a few really useful things: “reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away” was one of them. “Saint Paul would never go near Disneyland” was another. One of the main characters in ‘The Man in the High Castle’ the Japanese Businessman Nobusuke Tagomi experiences a momentary glimpse into an alternate reality on San Francisco’s Market Street, one where the Allies won the War, and must reflect on the Zen concept of holding two ideas – or in this case two parallel universes – in mind at once. If PKD had lived longer I’m sure he would have expanded on the idea of quantum superimpositions which have become a common motif not only in Science Fiction but in popular culture more widely thanks to the construction of the Large Hadron Collider).

Equally, not all Indian culture – in my admittedly limited experience – seems to be as precious about its gods and icons as its monotheistic equivalents. Hanuman, Siva and Kali can be super heroes and cool cult icons as well as a objects of veneration. The aura of what is orthodox and unorthodox veneration is fuzzy. The same is true of gurus like Sai Shridi Baba, and even for secular figures: especially for the author of the Indian constitution B R Ambedkar, who for his opposition to the caste system and advocacy of Buddhism as a more egalitarian alternative basis for culture has become a folk hero to lower castes. Ambedkar’s image appears on the street and in people’s homes the same way you might see pictures of Bruce Lee pinned up elsewhere in the world. No one thinks Babasaheb is a literal saint but his icon is treated like that of a holy individual because of its powerful meaning for the dispossessed people Ambedkar championed. Dr Ambedkar is a super hero.

Secularism in relation to secular or stage magic has always played a more active, rebellious and immediately useful role for people in India than it has in European cultures. The theatrical form of “rational recreation” – the debunking of spiritualism and seances on stage, along with magic tricks and feats of endurance, of the kind popularised by Harry Houdini – was a middle class attempt to improve the minds of the working classes who were felt to be susceptible to irrational beliefs in the occult and spiritualism. Charles Dickens – despite having his own magic act as the Unparalleled Necromancer Rhia Rhama Rhoos, after he bought the contents of an insolvent magic shop in London’s West End – acknowledged that this movement was lifeless because it didn’t offer the masses any diversion from their dreary reality, the desire that snake oil salesmen of the time were exploiting so successfully.

To this day, the “skeptic movement” in European cultures which draws on the tradition of stage magic and mechanical wonder established by Houdini and others, has maintained this dry and patrician attitude: that without the guidance of wise old white men, the mass of people may be drawn into incorrect modes of thinking such as Islam. Its figure heads are either unalloyed bigots like the late Christopher Hitchens, Richard Dawkins and the philosopher Daniel C Dennett, freemarket shills like Jillette Penn, or advocates of eugenics like James Randi. As the publisher and film-maker Mark Pilkington observed to me a few years ago at the first Nine Worlds festival in London, which has a skeptic “strand”, their entryism into SF fandom has a sinister inflection, as though people into spaceships and dressing up may be tempted to think the wrong things without the expert tutelage of an atheist, intellectual Eloi class. (My own warm feelings towards sincere religious faith and imaginative, free-thinking flights of fancy generally has remained uninfluenced by the onslaught of geek atheism, as is my Liberal agnosticism).

In former colonising countries, post-colonial skepticism and atheism is a conservative and reactionary movement, as is “steam punk” nostalgia for the 19th Century and the “nerd aesthetic” generally. Taken as a single cultural morass, these are all less concerned with liberating people’s minds than in berating and brow-beating them with unassailable facts in order to maintain the social order, and mainly to protect the predominantly white, middle class and almost exclusively male privilege of the university-educated hierophants who write all the code and copy, without which nothing in the former colonial societies now works.

This milieu is currently exemplified in Occidental cinema by the finger wagging Libertarian rationalism of Christopher Nolan’s piss-poor, killing-spree friendly, and ubiquitously popular oeuvre, which has managed to take the sense of wonder out of the Superman mythos – that you’ll believe a man can fly – replacing it with really long fights and speeches: you’ll believe that a man can break another man’s neck. (“The uniform is an iconic part of Superman’s character: let’s have them lying around in Kryptonian scout ships like Marriott towelling robes”. No doubt, we can look forward to Ben Affleck’s Bruce Wayne delivering post modern rants in ‘Superman Vs Batman: Dawn of Justice’ about how the free speech on display in ‘American Sniper’ and ‘The Interview’ are the values worth protecting from superstitious scum in Iraq and North Korea).

Atheist “churches” are advance cadres of gentrification of formerly working class parts of cities, replicating the same essentially conservative and controlling forces which built churches, mosques and synagogues a century ago, making sure that wealth and the impetus for change stay in the hands of a few self-appointed “community leaders”.

Allied activities to this are beginning to emerge in India: “crowd sourced” community clean-up efforts, and psychogeographic derives which have less to do with flâneurs and Situationism than with a social media-augmented brahmin caste scent marking poor people’s living space for later upgrades and commodification.

Whereas the skepticism in vogue in the Occident is basically about people obeying the rules and doing what they’re told, even if those rules are changing, the stage magic and rationalism of India has been a counter cultural, fertile, dirty and disruptive force since Phalke donned a cloak and waved a magic wand.

Guru busting in India is a dangerous and rebellious activity, which can get you killed. The demotic or popular form of magic – a kind of performance which has more to do with beggars and stuff that goes on in fun fairs than in exclusive, wooden panelled gentlemen’s clubs – is everywhere in India where there are poor people. Street kids juggle, tumble, walk ropes holding jars of water on their heads, at the intersections of busy roads and up and down train carriages; where ever they hope they can make a few rupees. It’s dangerous, pathetic, astounding, noble and heart breaking all at the same time. It shouldn’t be romanticised because at this level the circus is simply about people trying to survive.

Yet some successful stage magicians choose to immerse themselves in that struggle for survival: the maelstrom of incense smoke and mirrors outside a temple’s precincts, the public space in which people try to rise above their assigned caste, if only for a few moments. By demonstrating to large crowds how magic tricks work, Indian rationalists seek to encourage people to think for themselves rather than as they’re told to think.

In a culture where an esteemed and much-loved Bollywood star can release a mildly humourous film about an alien, which suggests that religious leaders may not be all they seem, only to have the cinemas attacked by tramps and rapists in saffron robes flanked by (obviously gay) goons with Hitler moustaches and haircuts made from licorice (did I mention really obviously gay?) – simply on the strength of the fact that the film challenges the priesthood’s authority, which only seems to stem from them being forced to recite the Bhagavad Gita since before they could walk – then challenging the basis of holy men’s ‘miracles’ on factual grounds becomes a form of popular insurrection.

By the power of the myths on which all religious conservatism is based in India – the authority of the priesthood to oversee the rituals, the temples, and legacies of nationalist and Hindu patriarchs – conservative forces can co-opt people’s existential search and deflect it to fascistic organisations. The BJP, RSS and similar fraternities subsume individuality in comforting and culturally reinforced lies, rather than responding to people’s basic quest for meaning and personal dignity: to answer the question of what it means to be a human, and – specifically – to be yourself in a country of more than one billion people.

In the recent blockbuster ‘Gunday’ our two muscular outlaw heroes recline on the same bed figuring out what to do next to progress the plot (we all know it’s going to be doing somersaults through slow motion clouds of Holi pigment, but we’re more textually literate than the protagonists who haven’t been to the cinema in India for the last decade, apparently). Their two, finely toned arses are sticking up in the air. The heroine enters their bedroom and sees what kind of a naan bread of bromance she’s about to be inserted into as filling: both their backsides are emblazoned with red sequined love hearts. This isn’t even homoerotic subtext so much as text. And yet, with the UN Secretary General saying India’s ridiculous colonial anti-LGBT law should be repealed, some people are still incredulous that the makers of ‘Gunday’ may be sharing a joke with their audience about what we’re all thinking and, indeed, about the private lives of many in the screen acting profession in India as elsewhere. (Just as Goa’s Chief Minister, of the ruling BJP party, genuinely thinks you can be ‘cured’ of being attracted to the same sex: a man who has not yet sought a cure for the shit stuck to his upper lip).

As a kind of secular mythology, Indian cinema – like Indian stage magic – offers an escape but into a world that’s sane and in proportion with people’s basic desires and needs. In this sense, between Dick and Jodorowsky, of the two Philip Dick is closer to the attitude to magic common in Indian film. Jodorowsky – despite drawing heavily on Indian and Asian mysticism and religious iconography in his films – is closer to the Western (and specifically Catholic) idea of God manifesting through a sacramental ritual. They’re both forms of escape, but one is an escape from a bewildering macroverse into the quiet, the personal, into what is emotionally real and meaningful to the individual. The other is a desire to transcend the personal and make contact with the bewildering totality of the divine.

Dick was a magician at finding nuance and cadence in tiny details, often in inanimate matter. He turned these into vast, emotionally and often mystically rich vistas. Ancient bugs in the soil on Mars were antagonists. An automated taxi cab driver bestowed folk wisdom.

Jodorowsky is a mystic like Philip Dick but he’s making mandalas at the other end of the scale entirely. Rather than imbuing intense meaning in tiny details, through prose, Jodorowsky fashions immense, baffling spectacles on the cinema screen. It’s not enough in a Jodorowsky movie to stumble on a village full of penitentes in the Mexican desert. They all have to be amputees and they all have to be dying and caked in blood. When a circus elephant falls down and dies, it must bleed to death through its trunk and we must see its death in a receding crane shot. Jodorowsky doesn’t do cadence or nuance. He makes huge patterns out of colours and violent images saturated with sexual and religious meaning, which we often see from up high and from God’s perspective. Jodorowsky puts the “gore” in “allegory”.

Both are doing a magic trick, the most basic magic trick there is which is to materialise something with an otherwise ineffable meaning as something apparently solid. Or rather, something which only exists in the their imaginations but which they fully realise for a fleeting moment in ours. Phil Dick did this trick using words. Jodorowsky does it through sound and coloured shadows projected on a flat surface.

For Dick, Trumbull’s version of the trick worked because he got to see something that existed only in his head up till that point – the Los Angeles of 2019 – realised with a dimension of solidity and realty which he never thought possible.

For Jodorowsky, Trumbull didn’t have the “right stuff” to fold the spacetime continuum and be one of his “spiritual warriors”. (Whereas a jayhawker of the imagination from the Ozarks, Missouri – Dan O’Bannon – did). In his mannerisms and demeanour, Trumbull was only a “technical” film-maker. To cut to the chase: he wasn’t obviously mentally ill, a certified genius like Jean Giraud or Chris Foss, or “out there” as Jodorowsky’s other intended collaborators on ‘Dune’ were: Orson Welles, Mick Jagger, Salvador Dali and Amanda Lear, David Carradine, H R Giger, Pink Floyd, Magma.

Jodorowsky is – quite clearly – wrong. Trumbull is far more than a technical film-maker, as anyone who’s made it through ‘Silent Running’ will attest. One of the most harrowing and gut-wrenchingly sad things ever committed to celluloid, Trumbull made maintenance robots into heroes only for George Lucas to turn them back into disposable comic relief a few years later.

Trumbull’s models and effects work on one level simply as patterns on the screen (a lot of the spaceships and machines in his films in the 70s look like Samsonite luggage) and capture the blocky, lifeless quality of industrial design at the time. ‘2001’ can feel like watching unclaimed bags going round and round forever on an airport luggage carousel. A mandala or a rangoli in India is about the act of making the pattern, the thought process and the gathering of people who create it. The pattern itself is lifeless and secondary to the ritual act, by people.

You could draw interesting parallels between the trippy escapism of European and American SF film in the latter half of the Twentieth Century, and a desire on the part of baby boomers to escape from the mechanical drudgery of the corporate careers of their parents in the post-World War Two period: a trip through a stargate to the next level of evolution thanks to a slab of black resin, or out on the highway with a cool girl at your side, in a cool vehicle that can do the Kesel run in less than 4 parsecs. Jodorowsky’s apostate Catholicism which is on display throughout his movies is a similar effort to run for the hills, rebelling against the primacy of the Counter Reformation and the institution of the Church in society by subverting the Sacraments.

An Indian attitude to escape in the same period seemed to have been totally different, however. The late 70s – when everyone in the West saw Star Wars – coincided with the Emergency rule period. Amitabh made his name then in a series of angry young man roles which expressed on screen what millions couldn’t, by law, give voice to: the violence and corruption of the new Empire, the Nehru dynasty, which had struck back. That meant you could only rely on your family. Society was crumbling all around in 1977.

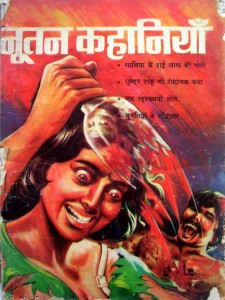

It could be argued that the pulp SF ‘Flash Gordon’ tropes that SF cinema drew on in the 70s in Occident didn’t exist in the same way in India. They weren’t identical, but from what limited investigation I’ve done over the last year or two it turns out that all the geek reference points are directly mirrored in the Indian subcontinent. To begin with, who needs Prince Valiant or Chewbacca when you have Lord Ram and Hanuman? Or King Arthur when you have the legends of Shivaji and Ashoka? There were (and still are) pulps in India, which provide exactly the same escapism and dubious diversion at the newsstand for sexually frustrated and bored commuters that they did in the USA from the 30s.

It could be argued that the pulp SF ‘Flash Gordon’ tropes that SF cinema drew on in the 70s in Occident didn’t exist in the same way in India. They weren’t identical, but from what limited investigation I’ve done over the last year or two it turns out that all the geek reference points are directly mirrored in the Indian subcontinent. To begin with, who needs Prince Valiant or Chewbacca when you have Lord Ram and Hanuman? Or King Arthur when you have the legends of Shivaji and Ashoka? There were (and still are) pulps in India, which provide exactly the same escapism and dubious diversion at the newsstand for sexually frustrated and bored commuters that they did in the USA from the 30s.

The most pulp-y and fan-fiction-influenced of all popular Indian films is ‘Mr India’: not only has it got the evil priest from ‘Temple of Doom’, Badmash #1 Amrish Puri as a blonde Gallagher brother and evil European Napoleon-figure, bent on domination of the subcontinent, he’s flanked by second banana super villains straight out of Western popular fiction. Under Mogambo’s regime, they’re reduced to cleaning out his acid-filled shark tank: “Dr Fu Manchu”, “Captain Zorro” and “Dr Watson”. (Poor John Watson, that jezail fragment must have finally worked its way from his “arm” to his brain). The hero – Mr India – is a mild-mannered music teacher who takes in orphans, confounds evil European colonisers, and stands up for the unrepresented masses using his only super power which is invisibility. Dr Ambedkar would have been proud.

There was also a long history of more serious or “straight” SF and imaginative fiction being produced in India for 200 years. There’s a great need – at least on the part of non-Indian readers like me – for more good overviews of this history but the task is mind-blowing, not least of all because Indian SF literature exists in many languages. I think this explains in part why no one’s attempted a thorough and over-arching appraisal of all of it so far, and why the considerable body of Indian SF literature hasn’t been more widely acknowledged, including within India itself.

There’s even been Indian fanfic, and not just any old fanfic: the greatest Indian film director Satyajit Ray was also a huge Conan Doyle fan, wrote a series of wonderful detective stories about Sherlock Holmes’ fictional biggest fan, Feluda, and also made two near-perfect films based on his stories.

The forms of escape in Jodorwsky’s vision of ‘Dune’, or ‘Star Wars’, or Ken Russell’s ‘Altered States’ didn’t have the same emotional resonance in India in the years following Independence. If you wanted to travel into a strange galaxy full of colourful, exotic, alien creatures you only had to walk out of your home, round the corner to the temple, church or mosque. For the majority, the life and death struggle against evil was the same thing as feeding, clothing and housing your family. If you wanted to expand your consciousness and travel to other dimensions, you only had to do what your grand parents wanted and to pay more attention to the imam or priest.

The kinds of escape that people wanted from movies in India from the 50s onwards was to somewhere pleasant, clean and welcoming. I think this explains why romance, flower gardens in Bangalore and the Swiss Alps, and musicals have continued to be so popular in India whereas they have fallen out of fashion elsewhere: singing and music are something within most people’s grasp but the magic of cinema perfects and distils the emotion of the moment. In a similar way, I imagine Phil Dick was responding to the ballet of flying cars and gas flares of a future L.A. which Trumbull’s team had made out of Dick’s words. Phil told the spceial effects team they had captured how the L.A. he imagined in the future had felt in his head, not how it had looked. If only Mr Dick could have heard Vangelis’s score too.